Chip shortage: What it means, why it’s happening, and when things will (hopefully) go back to normal

Tech runs on silicon. And we’re fresh out.

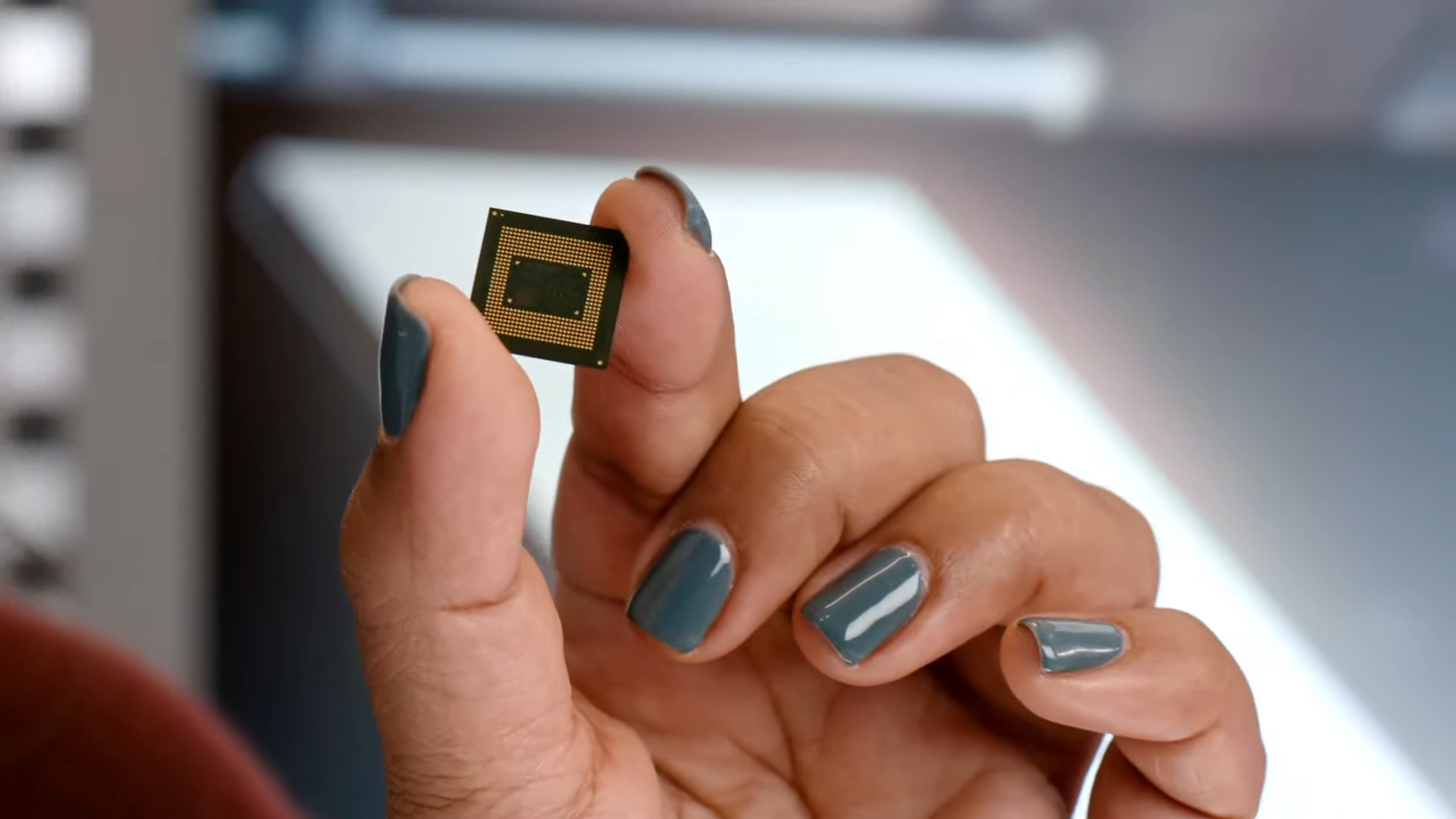

Technology relies heavily on semiconductors. These silicon chips power everything from smartphones to microwaves, relaying the information needed to do everything from snap photos to reheat last night’s lasagna. Unfortunately, these chips are in short supply these days. This has led to massive production slowdowns and price increases that both corporations and consumers are starting to feel.

From Apple and Microsoft to Dell, Samsung, and Sony, no one is immune. Everyone is feeling the effects of the shortage. And with a silicon shortage comes higher prices and reduced availability, something Apple reluctantly admitted in a recent sales call.

- Black Friday deals 2021— early discounts and what to expect

- Black Friday laptop deals 2021: Early sales, discounts to expect

- MacBook Air vs. MacBook Pro: Which Mac Should You Buy in 2021?

This isn’t just about smartphones and laptops. Some of the biggest automakers in the world have suspended operations and limited others due to a lack of semiconductors. Television manufacturers have spoken to investors about supply-side shortages that will certainly affect holiday shopping. Even the medical field is feeling the pinch, with 80 percent of those surveyed saying they are experiencing the effects of the shortage.

On the consumer side, ask anyone looking for a PS5, a console released a year ago, how that’s going. Sony says we may see shortages well into 2022.

About the only benefits we’ve seen from the silicon shortage is in the used car market, with pre-owned vehicles selling for record profits after manufacturers have failed to keep up with demand for new vehicles.

What Are the Causes of the Shortage

While it’s up for debate what the root cause of the issue is, the truth is that it’s most likely a multifaceted problem without a quick solution. Some experts believe the deficit has been years in the making, not the pandemic-related problem most are quick to assume.

One of many factors was a ban on the export of semiconductors to major electronics manufacturers like Huawei. The US-imposed ban forced these companies to outsource their chips to other countries, many of which simply couldn’t keep up with the demand and started to outsource some of the parts themselves.

Stay in the know with Laptop Mag

Get our in-depth reviews, helpful tips, great deals, and the biggest news stories delivered to your inbox.

Others turned to older technology, like the 200mm silicon wafer. Most semiconductors are built these days with 300mm silicon wafer, which can handle roughly double the throughput of its thinner sibling. This, too, is problematic as few factories have the tooling needed to manufacture equipment using the older technology, which further exacerbates the slowdown.

Aside from supply-side issues, we also have to consider record demand. With pandemic-fueled shutdowns keeping some factories from operating at full capacity, and a world full of people locked indoors — and buying more electronics than ever to stay busy — it’s easy to see that this is a difficult problem to overcome.

The COVID-19 Pandemic

While it’s easy to buy into the argument that the semiconductor shortage was years in the making, and not based solely on the pandemic, it would be disingenuous to say COVID didn’t play a part. With billions of people spending more time inside, the devices we rely on for both work and play are becoming an even more integral part of our lives. We’re buying more devices than ever and at a time where manufacturers can’t keep up with demand.

But it’s not just physical devices. Online companies need computing power to run applications and websites. Amazon, Google, and Microsoft need storage to maintain the backbone of the internet. To provide computing power, storage, and the technical essentials needed to run online businesses, we need… you guessed it, more silicon chips.

How Will Semiconductor Shortage Affect Our Lives

Everyone who has the most basic idea of how the economy works knows that prices go up as supply goes down. So, an inevitable effect of the shortage is an increase in the price of products reliant on semiconductors. The products most affected are going to be, well, everything. Everything from online services to your next car purchase is going to be affected. The only real question left is: by how much? We’ll all feel the pain in our wallets, but the length of the slowdown is the only real indicator we have in how much it will affect pricing. The faster things return to normal, the faster we reap the benefits as consumers.

Automakers, for example, have ceased or limited operations in some cases, citing a lack of semiconductors to power today’s technology-driven cars. Most apply the just-in-time principle to managing suppliers. This leads to fewer slowdowns and less wasted inventory. Without a massive inventory of parts to tide them over, stoppages are inevitable.

When the Experts Say it Will End

The consensus here is that there’s no consensus. What most experts agree on, however, is that the shortage will last into 2022, at least. Bain & Company, a global management consulting firm, is taking the optimistic route, stating that we'll stop feeling most of the squeeze next year.

Gaurav Gupta, a vice president at one of the industry's most respected analyst firms, Gartner, says that the shortage is likely to extend past the second quarter of 2022.

Others, though, are less optimistic. Some analysts believe we won’t see much relief until 2023, with a handful predicting that this is essentially the new normal; we’ll never go back.

Time will tell who gets it right, but what we know now is that matters of the supply chain are complex. Taking raw materials and turning them into semiconductors, and later finished consumer goods is a nightmare of interdependencies and short-term solutions require something in the range of six to nine months to implement.

One thing that’s certain is that we’re going to be feeling the effects of this for a while, so maybe it’s best to hold on to that iPad for another year.