The metaverse marginalizes disabled persons — how virtual worlds can be more inclusive

The metaverse is the future, but it’s leaving disabled persons in the past

The metaverse. Everybody’s favorite topic (besides NFTs). Since the internet entered the era of Web 2.0, the disabled have been pleading to take online classes and work online jobs. They were told, “It’s too complicated,” or “It’s not feasible,” but it’s painstakingly obvious that that was false.

- The best laptops of 2022

- Building the ultimate laptop for accessibility: Features to help those with disabilities

With the growth of cloud gaming, abstract concepts like virtual power plants becoming a reality, and the birth of satellite internet to deliver large amounts of data to the entire world, widespread metaverse adoption is inevitable. So let’s build a sandbox we all can play in (maybe without the sand).

VR headsets and controllers are not disability friendly

Before we examine what these virtual worlds should look like, we need to understand the challenges that plague the metaverse. If you are accessing the metaverse via a game like Fortnite or Minecraft, it’s not a problem because people can purchase adaptable keyboards, mouses, game controllers and remap buttons.

This equipment can often be expensive and difficult to obtain for a group that lives off social security benefits or has limited funds. Rightfully, the Xbox Adaptive Controller (XAC) was praised for making gaming more accessible, but many companies think the problem is solved or make their systems compatible with the XAC so they don’t have to innovate new hardware. But if the XAC ($100) is purchased alongside a new system like the Xbox Series X ($500), plus a few $60 games, and an adaptive controller to plug into the XAC (potentially hundreds of dollars), how feasible is it to make your conduit to a disability-friendly metaverse?

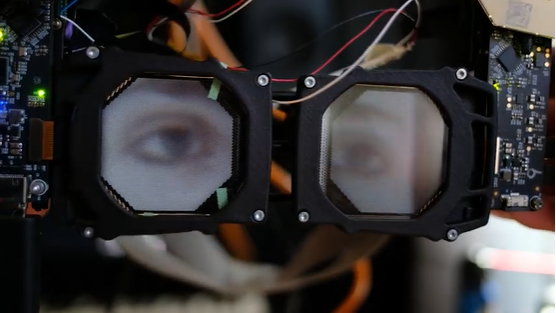

The real issues, though, come when you have to access the metaverse by way of VR headsets. The weight of VR goggles is simply too much. Some people’s neck muscles aren’t strong enough to hold their head up, never mind strapping it with clunky hardware. Hopefully, augmented reality glasses, or some other tech innovation, comes along to make trips to the metaverse more lightweight.

Another issue with VR sets is the controllers. The dual handles have buttons or joysticks that fit snugly in each hand, but some people may be missing a limb or don’t possess the dexterity to operate these controllers. The controllers also don’t have ports like the XAC, so a disabled person couldn’t even use a controller that works for them. There are VR headsets like the Oculus Quest 2 that have hand tracking, so some games can be played without controllers, but the technology is in nascent stages and is frustratingly sub-par.

This is not to mention that some neurodiverse people don’t have the mind-splitting ability to utilize controllers in different hands. Similarly, it may be difficult to control an avatar when there is a cognitive disconnect because you can’t see what your fingers are doing on the controller. Metaverse enthusiasts point out that in future versions, controllers will not be needed because a person will be able to move and use their limbs freely. This presents an entirely new set of problems: what if you can’t move your limbs the way you want and/or prefer a controller?

Stay in the know with Laptop Mag

Get our in-depth reviews, helpful tips, great deals, and the biggest news stories delivered to your inbox.

In addition to all of those obstacles, the most obvious matter is ‘What about the blind or visually impaired?’ On a pragmatic level, how are the two screens of VR glasses (one for each eye) supposed to work together to create an immersive, three-dimensional picture if you can only see out of one eye? How can such a visual medium create a virtual utopia for the legally blind?

If the metaverse is going to be a future workplace and socializing spot for everyone, the deafblind aren’t even a blip on the radar. How will someone who navigates the world by the tactile touch of Braille explore the endless landscapes of the metaverse? Many would conveniently say “Maybe the metaverse is meant for the deafblind,” but they are part of the all in ‘accessible for all’. They are part of our virtual yonder. Haben Girma is a deafblind woman who graduated from Harvard Law, spoke at conferences, wrote articles for big publications, and traveled extensively. She is someone that should be in any metaverse — and is an example of what the deafblind are capable of.

The metaverse needs better representation of disabled persons

The metaverse has able-bodied avatars, so users will erroneously assume that everyone can walk, talk, see and hear like the ‘normal’ majority. Certainly, there will be people who choose an avatar that is more of an ideal body, but what about those that already recognize their bodies as whole? What about the disabled who just want to be themselves? The reason we can customize skin color and gender in games today is because minorities felt there were no accurate portrayals of themself on screen. Why not do the same thing by giving an avatar a mobility aid, hearing aid or white cane? If everyone has an opportunity to create a digital twin of themself, why wouldn’t a disabled person want a chance to see themselves represented in the metaverse?

Like we have seen in film and television, representation matters. Being acknowledged can inspire confidence in an individual while providing an entire community with a sense that they belong in that world. The bones of this inclusiveness is being built at the World Wide Web Consortium. It employs several people with disabilities to help create the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG). The WCAG sets standards for austere elements of the internet like text sizes, font contrasts, etc. This might not seem like a big deal, but it is for thousands of disabled people. It provides a set of blueprints to make various elements in tech accessible.

The only problem with the WCAG is that they are voluntary, but they’re also a law under Section 508 for federal employees and their contractors. This causes confusion for when the WCAG must be applied. And, of course, private companies only have to follow ADA (Americans with Disabilities Act) Title III, which has not been updated to mention rules for internet accessibility. The lone saving grace for the disabled has been that courts and /industry experts repeatedly confirm that WCAG provides a reasonable accessibility standard.

However, WCAG is not the only blueprint for improving digital accessibility. Perkins Access (out of The Perkins School for the Blind) cites XR Accessibility User Requirements (Also created by the organization that makes the WCAG), XR Accessibility by Berkeley Universal Design for Learning, Resources for accessible XR hosted by XR Access, and the XR Association Developer's Guide: An Industry-Wide Collaboration for Better XR as good resources to create a more equitable metaverse. And software engineers working on gaming worlds can adhere to the Game Accessibility Guidelines and the Xbox Accessibility Guidelines (XAG for short). But these are also unofficial practices that are written and maintained by (mostly) able-bodied industry experts. With much of Congress in their 40s or 50s when the internet became popular, who knows when there will be laws for creating accessible 3D experiences.

The metaverse could be a haven for disabled persons

Once the disabled can access the metaverse, there are many reasons for optimism. For example, everyone’s involvement can be personalized. If a concert is too loud, an individual can turn their private volume down. Someone who is hard of hearing can turn the captions on their screen and make them as large or small as they want — without changing everyone’s experience. You’ve heard promises of grandeur from Mark Zuckerberg and the like before, but when users in metaverse-style games like Roblox raise awareness on issues of accessibility, it is hard not to feel hopeful about the metaverse’s prospects. Unlike in the physical world, when a user brings an accessibility problem to light it is not interpreted as a problem, but rather a design opportunity. This friendlier perspective is because the problem won’t take money to fix, just different code.

These single pieces of feedback are like thousands of pebbles being thrown into a digital ocean that can cause ripples across the developer community, catalyzing changes in current and future projects. AR Apps like TapTapSee, which allows users to point their phone’s camera at an object and have it described to them, could galvanize a movement of better accessibility in the metaverse. These innovations only scratch the surface of what creative minds can accomplish if we build with accessibility at the forefront of our minds.

It should be noted that there are talented hardware and software engineers working on accessibility in the metaverse right now. However, the whole situation is eerily similar to how the people designing the AI everyone uses everyday failed those with dark skin. It’s on us to lay the foundation of an accessible metaverse so we can all play inside it. We don’t need a metaverse that meets some arbitrary bare minimum; we should be producing worlds that are far superior to the physical world. As we have seen from Covid-19, anyone can acquire a disability without warning, so let us use the technology at our disposal to create an accessible metaverse.