The M3 gamble: How Apple's bet shaped its silicon future

Apple has kept a measured approach to updating its M-series chips, but the transition from M3 to M4 is happening at an unprecedented pace.

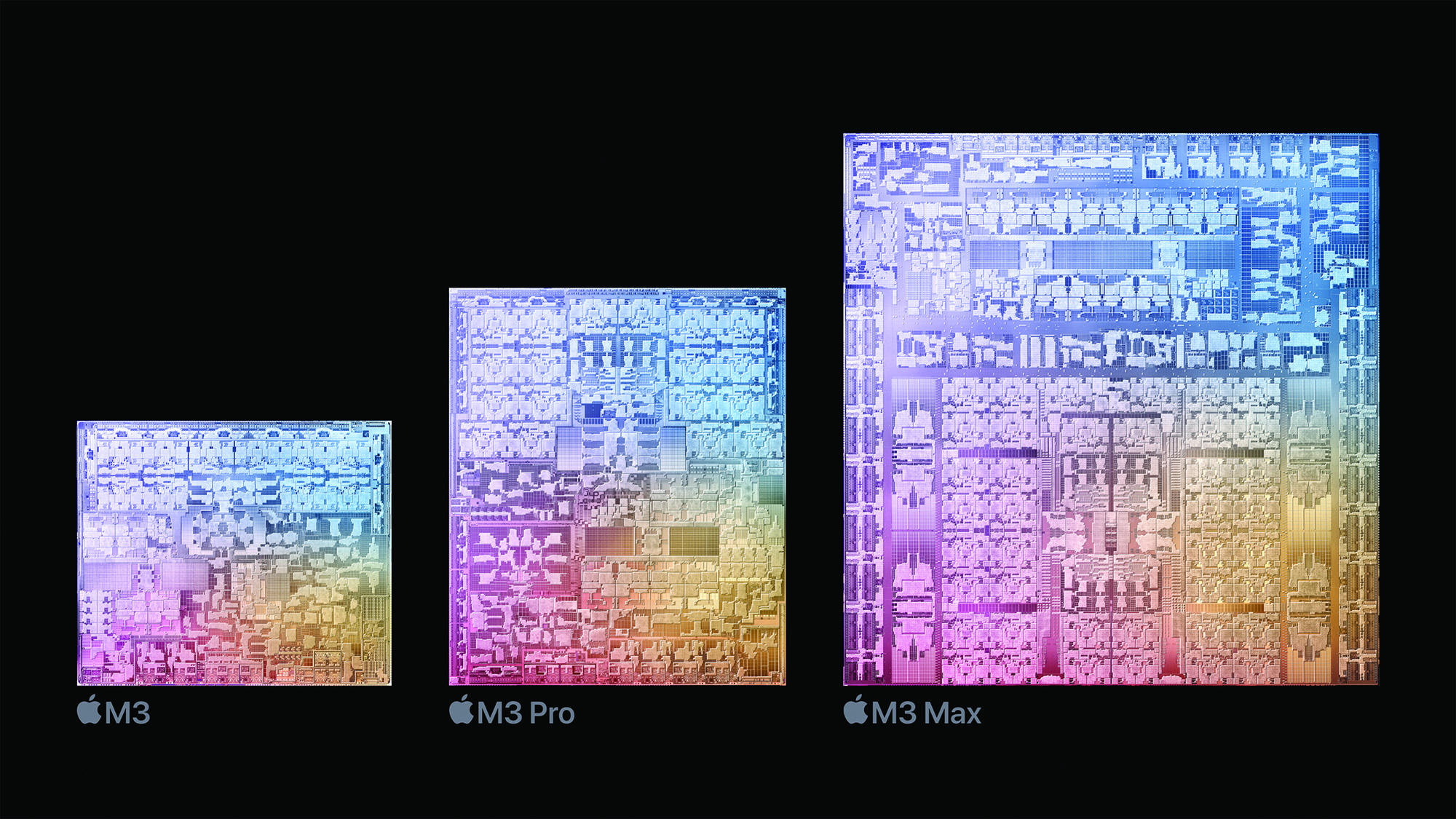

Apple’s transition from the M2 to the M3 was a huge leap forward in its silicon strategy. One that would push its performance and efficiency further than ever before as the first chip built on a cutting-edge 3-nanometer (nm) process, N3B, from Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC). This promised faster CPU and GPU performance and improved power efficiency, alongside a whole host of other features.

Johny Srouji, Apple’s SVP of Hardware Technologies, touted the M3 series in October 2023 as “the most advanced chips ever built for a personal computer” in an official Apple press release because of its new GPU architecture, faster neural engine, and more unified memory.

However, this transition — while a success in bringing all-new levels of performance to consumer devices — quickly became problematic for Apple, leading to what is widely recognized as the shortest lifespan of any microchip in Apple’s history.

Strangled by low yield rates

Apple’s move to 3nm fabrication seemed logical at first glance. The company had previously seen great success with TSMC’s 5nm process, which powered M1 and M2. In addition, shrinking transistor sizes theoretically bring greater power efficiency and performance gains, allowing Apple to maintain its competitive edge over Intel and AMD, which were still on 5nm processes then.

Apple worked with TSMC to develop the N3B variant of the 3nm process. N3B was essentially a trial node that, while offering high transistor density, suffers from lower yields and is incompatible with TSMC’s future 3nm refinements.

As it transpired, N3B came with serious production problems, primarily due to its aggressive design rules and the introduction of new components like self-aligned contacts to insulate against electrical shorts. These factors contributed to lower yields and challenges in metal stack performance. Compounding these issues was Apple’s desire to be the first to market with a 3nm chip, leading the company to secure TSMC's entire initial production of 3nm chips.

This was a calculated risk by Apple that ultimately backfired, exposing the company to the inherent risks of early adoption, including lower initial yields and higher production costs. TSMC’s yield rates for these chips were reportedly as low as 55% during early production, meaning that almost half of all M3 chips produced were defective. It wouldn’t be surprising if this low yield rate made the M3 one of Apple's more expensive chip productions, as each wafer was already drastically costlier than its 5nm predecessors.

Stay in the know with Laptop Mag

Get our in-depth reviews, helpful tips, great deals, and the biggest news stories delivered to your inbox.

Apple’s A17 Pro chip (in the iPhone 15 Pro) and the Mac M3 chips were the first mass-market 3nm chips, according to Apple, so the company encountered these process node challenges head-on. However, these extremely low production yields were unforeseen, forcing Apple and TSMC to negotiate, as one observer characterized it, a “sweetheart deal,” whereby Apple only paid for working chips instead of whole wafers.

The 3-nanometer process came with serious production problems.

This was an unusual concession for the semiconductor industry, where the standard practice is for chip designers to purchase entire wafers — the thin slice of semiconductor material that acts as a base for integrated circuits like the M3 — regardless of how many functioning chips (“dies”) are produced from each one.

This is a fundamental aspect of the business model that fairly distributes risk between foundries and their customers. In Apple’s case, however, they had reportedly booked some 90% of TSMC’s 3nm production and this pricing arrangement was critical for them to offset the financial impact of M3’s low yield rates.

In response to these problems, Apple quickly pivoted to TSMC’s N3E process (the second variant of TSMC’s 3nm node) for the A17 Pro in late 2025 for late-cycle iPhone 15 Pro production. This pivot protected its profit margins without requiring significant chip specification changes and enabled volume production of lower-tier chips like the A18, thereby expanding 3nm adoption across Apple’s iPhone 16 lineup. However, a $1 billion redesign of CPU clusters and memory controllers for the M3 family was needed.

Inconsistencies in the M3 lineup

This split between the N3B and N3E processes for M3 production created inconsistencies in the lineup. The M3 Pro, for example, which was built on the earlier N3B process, actually had 25% less memory bandwidth than its M1 and M2 Pro predecessors (150GB/s vs. 200 GB/s). Apple achieved this by using a narrow memory bus, which likely improved chip yields, reduced die size, and even cut down the CPU core count, with six performance cores in the M3 Pro vs. eight in the M2 Pro.

Apple's atypical downgrades in spec were curious and drew notice since, as you would expect, new chip generations are only meant to go up in capability.

Likewise, the lower-bin M3 Max had its memory bandwidth capped at 300GB/s instead of the full 400GB/s that previous iterations of Max chips had. These atypical downgrades in spec were curious and drew notice since, as you would expect, new chip generations are only meant to go up in capability. Although there has been no official confirmation, it’s suspected by some that Apple made these design tweaks to accommodate the realities of the N3B process and prioritize manufacturability over brute-force specs.

The impact of these N3B process woes was evident in the performance and production of M3 chips. Performance-wise, the M3 series still delivered generational gains, especially in GPU capabilities, but these were uneven. The base M3 saw a healthy ~15% single-core uplift over M2 thanks to the new 3nm cores, but its reduced core count overshadowed the M3 Pro’s multi-core improvements—and in some tasks, the M2 Pro could almost match it.

On the manufacturing side, the low yields heavily constrained output, forcing Apple to make tough choices.

On the manufacturing side, the low yields heavily constrained output, forcing Apple to make tough choices. The company seemingly held back its high-end Macs until the 3nm process could mature, with machines like the Mac Studio not appearing with M3 architecture until March 5, 2025. The Mac Pro is still shipping with the M2 Ultra at the time of publication of this report.

The MacBook product line also faced delays, with Apple analyst Ming-Chi Kuo commenting in September 2023: “It seems that Apple will not launch new MacBook models (equipped with M3 series processors) before the end of this year.”

Performance shortfalls all around

At the high end, the M3 Max was well received for its massive GPU performance boost, with a 40-core GPU outperforming previous MacBook Pro models in intensive creative workloads. However, Apple’s decision to skip an M3 Ultra model on the N3B process variant — which would have powered high-end Mac Studio and Mac Pro desktops — was a notable omission at the time.

Beyond raw performance, efficiency and thermal management have become notable talking points among users. The iPhone 15 Pro’s A17 Pro chip was widely criticized for overheating issues, leading to speculation that M3 chips suffered from similar inefficiencies. “Users of the iPhone 15 have reported that after 30 minutes of use, the mobile processor reaches temperatures exceeding 48˚C... Many have pointed their finger at TSMC’s 3nm process,” observed Robin Mitchell on the engineering news website Electropages.

All this illustrates how the choice of N3B vs. N3E impacted the M3. Apple started M3 production on the bleeding-edge N3B to get 3nm Macs out sooner but faced yield and efficiency hurdles, resulting in a somewhat transitional product.

A stepping stone to the M4?

Apple has historically maintained a measured, iterative approach to updating its M-series chips with a roughly 18-month cycle between generations. However, the transition from M3 to M4 is happening at an unprecedented pace, suggesting that Apple is eager to move past the issues faced with M3.

TSMC’s transition from the N3B process to the N3E process is at the core of this generational shift. Unlike N3B, which only achieves ~55% yields, N3E offers ~70-80% yields and improved manufacturability, allowing for lower production costs and more consistent performance.

It’s also not too farfetched to consider that perhaps this was Apple’s game plan all along: To introduce an early 3nm chip (A17 Pro in the iPhone 15 Pro and the M3 for Macs) as a transitional design — a necessary early step to develop the “first 3nm,” but not the design Apple considered fully optimized.

This sentiment is reflected in how quickly Apple pivoted its lineup beyond M3 and excluded many mainline products — Mac Mini, Mac Studio, Mac Pro — from the M3 generation so that their next update would launch with M4 chips instead.

While Apple hasn’t publicly criticized its own M3 chips (on the contrary, its press releases praise M3’s advancements), there are hints of internal acknowledgment of challenges. For instance, the A17 Pro chip, which is built on the same 3nm family as M3, had well-publicized thermal issues in the iPhone 15 Pro launch, which some insiders attributed to the rushed 3nm process and others to a bug in iOS 17.

While Apple has not publicly criticized its M3 chips, there are hints of internal acknowledgment of challenges.

Indeed, Apple’s chip engineers had to design two versions of the A17/M3 cores — one for the early N3B node and another for the more mature N3E node — essentially a do-over for better efficiency.

There’s also some interesting context if you read between the lines. When Apple (surprisingly) introduced an M4 chip in the iPad Pro just six months after the M3 launch, it raised eyebrows: “The M3 chip and its siblings were the first Apple silicon generation to use a 3-nanometer fabrication process. But that process was lacking, as the M4 arrives via an entirely new, reconfigured method,” observes Ryan Christoffel in 9to5Mac, adding, “It seems there were continuing inefficiencies and yield issues with that original process, and Apple wasn’t content dealing with those problems any longer.”

Notably, Apple emphasized that the M4 was built on “second-generation 3-nanometer technology, implying the first-gen 3nm in M3 had shortcomings. A report from EE Times had earlier highlighted that TSMC was “straining to meet demand” for 3nm chips and that yield struggles were impeding volume production.

The result was an unusually fast generation leap, marking what one outlet characterized as an “aggressive update schedule” compared to the more typical 18-month cadence seen with the M1 and M2.

The chart above shows how M4 performance compares to other similar laptops, including a MacBook powered by the M3 chip.

Transitioning to the M4

Despite all the challenges faced with the M3, Apple’s control over its silicon roadmap remains a massive advantage. These challenges, however, exposed the risks of being too aggressive with new manufacturing nodes.

By going all-in on TSMC’s N3B process, Apple faced low yields, higher costs, and unexpected performance trade-offs — a stark contrast to the smooth transition seen between the M1 and M2. This aggressive push for early 3nm adoption was driven in part by competition, as other industry players like Intel, with the Xeon 6 and Core Ultra 200V Lunar Lake processors, and AMD, with the EPYC Turin, were also integrating 3nm technology.

Looking ahead, Apple has already invested $2.5 billion in TSMC’s Arizona fab, highlighting the company’s commitment to securing long-term supply chain stability.

Ultimately, the M3 transition will likely be remembered as an ambitious and successful experiment

While the Arizona facility is not expected to produce Apple’s leading-edge chips immediately, this suggests a more strategic, controlled approach to future chip development, potentially avoiding another rushed transition like M3. It’s worth noting that TSMC has experienced significant staffing issues at the Arizona facility due to alleged worker abuses and differences in workplace regulations.

At the same time, Apple will prepare for its next major process: the transition to 2nm chips. TSMC has confirmed that N2 production will begin in the second half of 2025, with Apple likely among the first customers. However, the question remains: Will Apple once again take a risky early-adopter approach, or will it wait for a more refined version of the node, such as N2P, before fully committing?

That said, Apple has not abandoned the M3 entirely. While it skipped the chip in key product lines like the Mac Mini and Mac Pro, it did introduce an M3 Ultra Mac Studio and iPad Air in early March 2025. This naturally raises the question of why Apple would continue to release select M3 devices while transitioning to M4 elsewhere. The likely answer lies in production scalability, with the Mac Studio and iPad Air being lower-volume products compared to MacBooks and iPhones, making low-yield constraints less of an issue.

Ultimately, the M3 transition will likely be remembered as an ambitious and successful experiment, but not without its challenges — and ultimately, a necessary step in Apple’s silicon evolution. With the announcement of the M4 MacBook Air potentially putting Apple’s M3 lineup on the back burner, it’s not unreasonable to wonder whether Apple might secretly be glad to move on.

The 2024 MacBook Pro with an M4 processor features 512 GB of RAM and starts with 16GB of unified memory. In our review, it received an ultra-rare 5 out of 5 stars and our Editor's Choice award. And you won't have to look for an outlet very often as our review spec of this laptop went more than 18 hours between charges.

More from Laptop Mag

Luke James is a freelance writer from the UK. Although he primarily works in B2B assurance and compliance, he moonlights as a tech journalist in a bid to stay sane. He has been published in All About Circuits and Power & Beyond, where he focuses on the latest in microchips and power electronics, and consumer tech publications like MakeUseOf.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.